Looking outside the Box

Discovery of EM Spectrum Revisited

The more we look, the less we see.

That’s because we continue to look in the wrong part of the EM spectrum.

Visible light spans a paltry 3800-7000 Å. And our eyes ‘blind’ us to the depth of physical experience offered by the rest of it.

So, that’s what we will revisit today.

The discovery of EM spectrum beyond human perception.

Maxwell Correction to Ampère’s Law

The story begins with an edge case that others before Maxwell had completely missed.

Ampère’s Circuital Law related the magnetic field B around a loop with the amount of current passing through it.

To be precise, it states that the closed loop integral of the magnetic field (over a curve C) is proportional to the current piercing a surface S.

[This current can equivalently be expressed as a surface integral of the current density J (current density flux) over the surface S.]

\[\oint_{C} \mathbf{B}\cdot d\mathbf{l} =\mu_{0}I=\mu_{0}\iint_{S}\mathbf{J}\cdot d\mathbf{S}\]This curve C can be arbitrary, but must be closed. And C must be the boundary of the open surface S.

Think of C and S like the lip and body of a balloon respectively.

The lip and body of the ballon can be thought of as C and S respectively.

Essentially, the law holds regardless of whether this balloon is inflated or not.

And it is exactly this fact that Maxwell used to point out the discrepancy in this law.

Capacitor Argument

Consider a charging parallel plate capacitor.

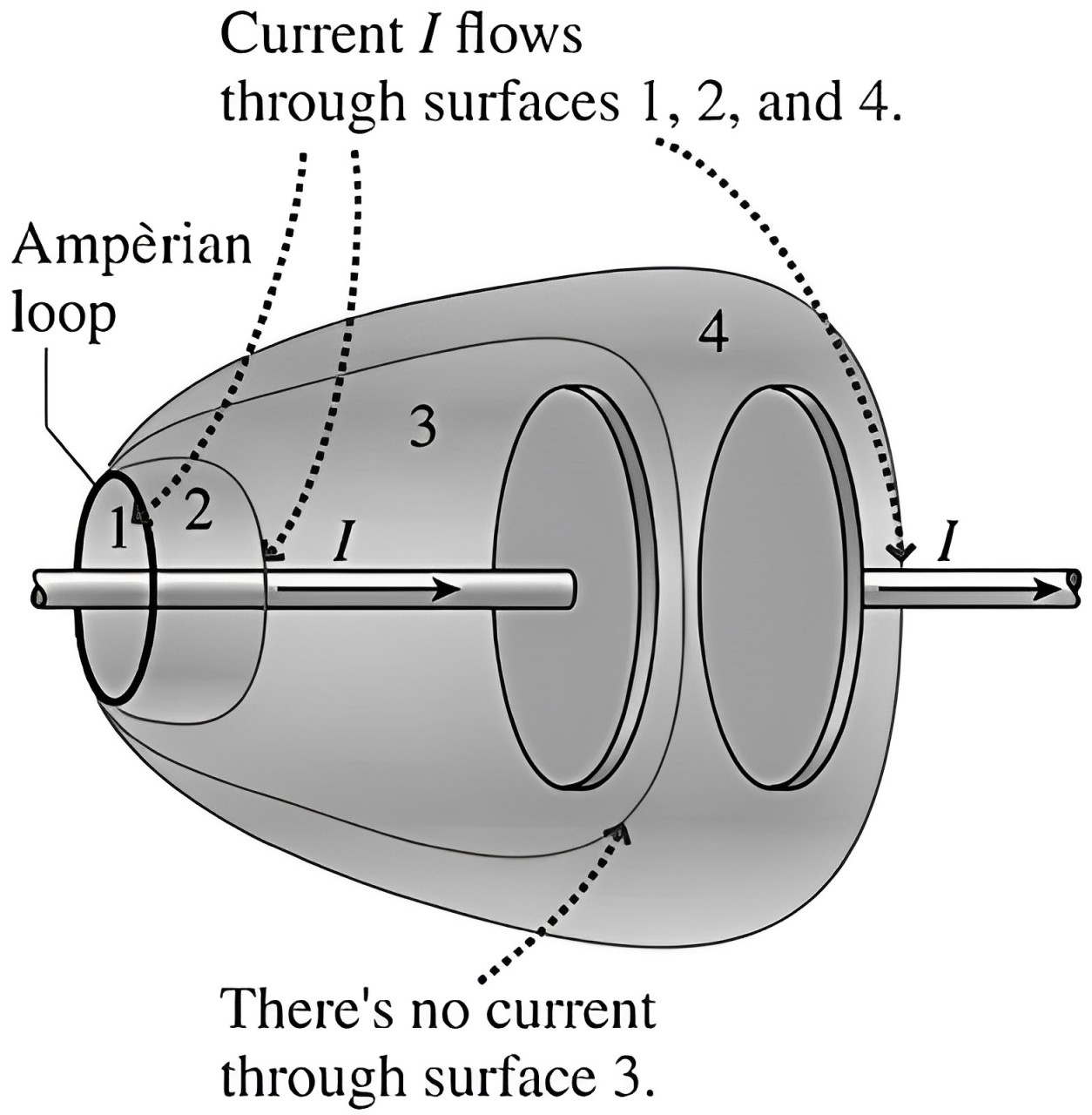

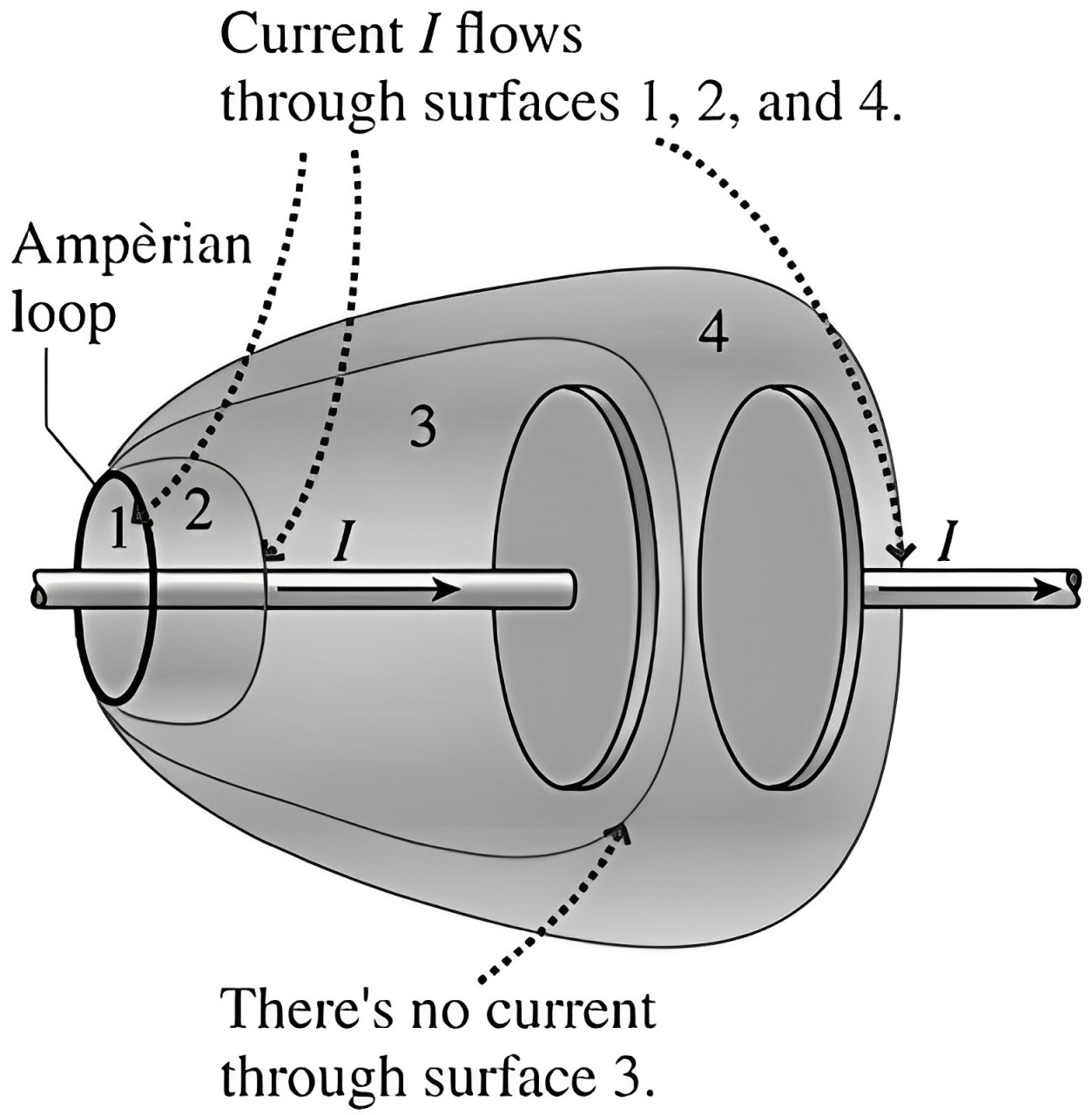

Now imagine 4 hypothetical balloons, covering the plates of the capacitors as shown in the figure.

Notice that each of these ‘balloon bodies’ (surfaces 1, 2, 3, 4) is bound by the same ‘lip’ (Ampèrian loop).

So, by our ‘uninflated-inflated balloon’ law (Ampère’s Circuital Law), since the LHS is same, the RHS must also be the same.

That is, all of these surfaces must have the same piercing current I.

But, evidently, the current I does NOT pierce (enter and exit) the surface 3. It is only entering the surface.

To remove this inconsistency, Maxwell proposed the **existence of a quantity called the **displacement current which ‘flows’ between the plates of the capacitor.

For the law to hold true, the amount of ‘displacement current’ exiting must be equal to the ‘conduction current’ (conventional current) I entering.

\[I = I_{D} = \frac{dq}{dt} = \epsilon_{0}\frac{d\phi_{E}}{dt}\]Where ΦE is the electric flux through the surface in consideration.

Think of it as the amount of electric field crossing the body of our balloon 3.

Taking this into account solves our problem, and modifies the law as follows.

\[\oint_{C} \mathbf{B}\cdot d\mathbf{l} =\mu_{0}(I+I_{D}) = \mu_{0}\left(I+\epsilon_{0}\frac{d\phi_{E}}{dt}\right)\]Existence of EM Waves & their linkage to Light

At this point, Maxwell could have stopped his intellectual ploddings and called it a day.

But, I’m glad he didn’t.

Cause what followed blew his mind.

And, the mind of every other physicist at the time.

Modification of Ampère’s Circuital Law gave us the missing piece in the puzzle of theory of Electromagnetism.

Let’s look at all of the equations at once.

Gauss’ Law

\[\phi_{E} = \frac{q_{enclosed}}{\epsilon_{0}}\]Gauss’ Law for Magnetism

\[\phi_{B} = 0\]Faraday’s Law

\[\Gamma_{E} = -\frac{d\phi_{B}}{dt}\]Ampère-Maxwell’s Equation

\[\Gamma_{B} = \mu_{0}\left(I+\epsilon_{0}\frac{d\phi_{E}}{dt}\right)\][Gamma Γ has been used to represent the closed loop integral of E and B]

I have condensed the integrals into the physical quantities they represent.

This is done in part to make it look less scary. But, more importantly, it also helps us focus on the bigger picture.

Before the modification of Ampère’s law, we just had E and the rate of change of ΦΒ related to one another.

This led to a sort of asymmetry between E and B.

That is, E and B were interdependent. Yet, only a changing B could produce E.

With the appropriate modification in place, it was apparent that even a changing E could produce B.

But, wait…

If a changing E could produce B, what will happen if this B itself starts changing with time ?

Well, it further produces E. Which itself changes, producing yet disturbance in B and so on and so forth.

So, a disturbance created in either of the fields is carried over by this mechanism in the form of a wave.

This is precisely what Maxwell realised.

By combining his newly modified equation with others, he obtained a wave equation for this ‘electromagnetic wave (EM wave)’.

Electromagnetic Wave equation

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electromagnetic_wave_equation)

And like all waves, this EM wave too had a velocity of propogation.

But, for this wave, the velocity wasn’t just any old number.

It was, exactly equal to the speed of light.

\[c =\frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu_{0}\epsilon_{0}}}\]The result was too good to be true.

But unlike most things of such sort, it really turned out to be the case.

Light is literally just an EM wave !

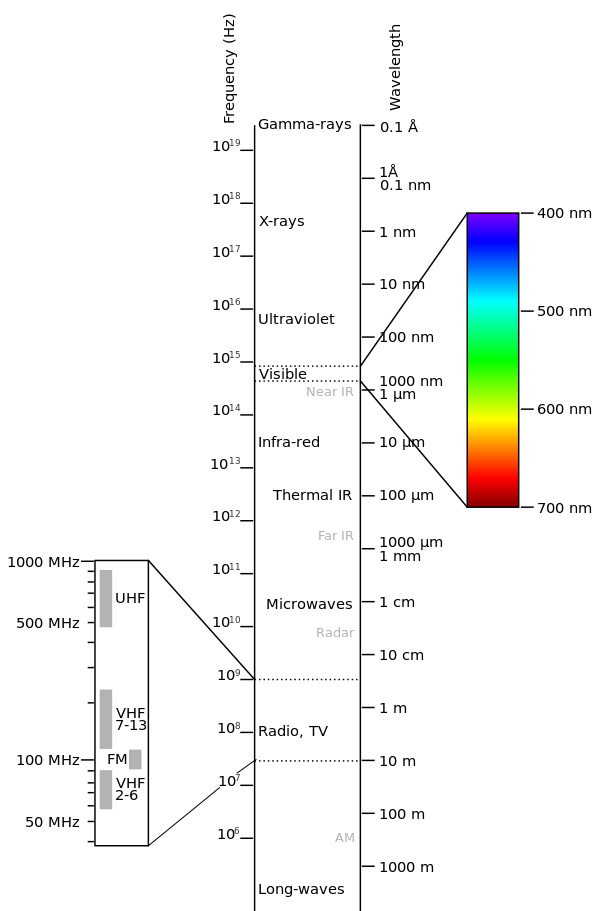

Visible light is a sliver as compared to the entire EM spectrum.

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electromagnetic_spectrum)

But, as discussed earlier, in the large expanse of wavelengths, light is all but a small sliver.

Infrared

1800 - Frederick Herschel

Herschel did more than just discovering Infrared waves.

Herschel unified our conceptions of Heat and Light.

Despite having no formal scientific training, he had observed features on the Sun’s surface for a number of years. And being able to observe sunspots with a large telescope without damaging his eyes had long been a challenge.

Herschel was experimenting with different combinations of colored and darkened glass.

In a 1794 paper presented to the Royal Society, he noted :

‘What appeared remarkable was, that when I used some of them, I felt a sensation of heat, though I had but little light; while others gave me much light, with scarce any sensation of heat.’

Herschel thought that different colors might ‘have the power of heating bodies very unequally distributed among them.’ He further reasoned that if the heating power were unequally distributed, the illuminating power might be as well.

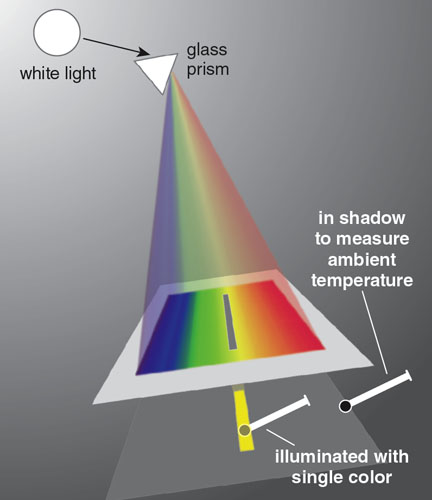

Drawing on his experience making telescopes, Herschel made a spectroradiometer.

Spectroradiometer measures the magnitude of radiant power (radiant energy emitted, reflected, transmitted, or received per unit time) at different wavelengths.

It consisted of three components - a prism, a small cardboard panel with a slit, mercury thermometer

The prism was set in a window to catch the sunlight. It directed and dispersed the colors down onto a table. The slit of the cardboard panel was wide enough for only a single color to pass through.

Setup used by Herschel to discover infrared waves.

(Source : https://www.americanscientist.org/article/herschel-and-the-puzzle-of-infrared)

With his device set up on a sunny day, Herschel methodically took temperature measurements.

The ambient temperature averaged 43.5⁰ F.

Herschel positioned the measuring thermometer in the band of colored light for each reading. He took a series of measurements, starting with red.

Red, Green and Violet colours gave an average reading of 6.875⁰ F, 3.25⁰ F and 2⁰ F above ambient temperature.

This data, Herschel believed, proved his hypothesis about heating being unequally distributed.

Yet, something about the temperature readings bothered him.

Unexpectedly, the measurements also showed a trend, instead of a peak.

The heating was greatest in red, but the curve did not appear to reach a maximum in the visible spectrum. He even detected a temperature one degree higher than that of red light.

The readings seemed to point somewhere in a dark region beyond red.

Since this region lay outside the visible spectrum, then the heating was not from light but from something else.

In 1800, when Herschel published these results, he used the expression ‘invisible light’ for this phenomenon.

And it is exactly this ‘invisible light’ beyond the red light that we call the infrared radiation.

Ultraviolet

1801 - Johann Ritter

Many of Ritter’s experiments were concerned with electricity or electrochemistry.

But, that’s not what he is most remembered for.

His biggest achievement was the discovery of the ultraviolet radiation.

Inspired by Herschel’s extension past the red region of visible light, Ritter speculated another invisible radiation beyond the violet end.

To test this, he began working with silver chloride (AgCl).

Interestingly, AgCl is decomposed by light.

And more importantly, the speed at which it decomposes varies with the colour of light used.

Ritter confirmed that violet light was more effective than red in achieving this result.

Moreover, he demonstrated that the fastest rate of decomposition occurred with radiation that could not be seen but that existed in a region beyond the violet.

Similar to Herschel, Ritter initially referred to this novel radiation as something exotic.

He called it ‘chemical rays’.

But, just like ‘invisible rays’, the term faded out. And we eventually stuck to ultraviolet radiation.

Microwaves and Radiowaves

1887 - Heinrich Hertz

Hertz received his professorship in 1886.

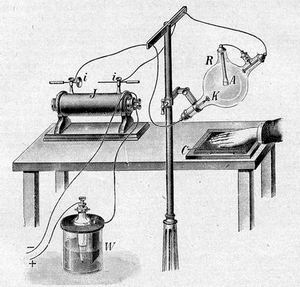

Then, he started experimenting with a pair of Riess spirals.

Riess spirals (or Knochenhauer spirals), are a pair of spirally wound conductors with metal balls at their ends. Placing one above the other forms an inductor.

While discharging a capacitor (specifically a Leyden jar) into one of these coils, a spark was produced in the other coil.

This gave Hertz an idea to build an apparatus and experimentally prove Maxwell’s theory of Electromagnetism. He used a dipole antenna consisting of two collinear one-meter wires with a spark gap between their inner ends, and zinc spheres attached to the outer ends for capacitance, as a radiator.

The antenna was excited by pulses of high voltage of about 30 kilovolts applied between the two sides from an inductor (Ruhmkorff coil).

Apparatus used by Hertz to discover Radiowaves and experimentally prove Maxwell’s theory.

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heinrich_Hertz)

Hertz received the waves with a resonant single-loop antenna with a micrometer spark gap between the ends.

Yet, he was unsure whether this phenomenon was actually the result of electromagnetic waves predicted by Maxwell.

Between 1886 and 1889 Hertz conducted a series of experiments to investigate the same, and ended up proving the hypothesis. Hertz measured these waves and demonstrated that the velocity of these waves was equal to the velocity of light.

Hertz also measured the electric field intensity, polarization and reflection of the waves.

These experiments established that light and these waves were both a form of electromagnetic radiation obeying the Maxwell equations. Along with discovering a new kind of radiation, the German physicist put a seal on the physical existence of his contemporary’s radical new idea.

The particular waves produced by Hertz are now called radio waves.

X-Rays

1895 - Wilhelm Röntgen

Röntgen worked on light emissions produced by discharging electrical current in ‘Crookes Tubes’.

These were glass bulbs, evacuated of air, with positive and negative electrodes, which display a fluorescent glow upon the passage of a high voltage current through it.

He was particularly interested in cathode rays and in assessing their range outside of charged tubes.

On November 8, 1895, to avoid undesired environment luminosity, Röntgen covered the Crookes tube with the black cardboard hood as well as he darkened the laboratory room.

He observed that the green fluorescent light caused a platinobarium screen 9 feet away to glow.

Apparatus used by Hertz to discover X-Rays

(Source : http://www.fazano.pro.br/ing/indi147.html)

He concluded that the fluorescence must be caused by invisible rays originating from the Crookes tube.

Further experiments revealed that this new type of ray was capable of passing through most substances, including the soft tissues of the body, but left bones and metals visible.

Röntgen used this to create a photographic film of his wife Bertha’s hand, with her wedding ring clearly visible.

Photographic film of Röntgen’s wife, Bertha’s hand with a ring, produced on Friday, November 8, 1895.

(Source : https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200111/history.cfm)

In January 1896 he made his first public presentation before the Würzburg Physico-Medical Society. He followed his lecture with a demonstration, making a plate of the hand of an attending anatomist.

This new discovery was proposed by many to be named ‘Röntgen’s Rays’.

But, the brilliant physicist himself stuck to a much more humble name, to underline the fact that their nature was unknown : X-Rays.

Gamma Rays

1900 - Paul Villard

Radioctivity was discovered by the Curies in 1898.

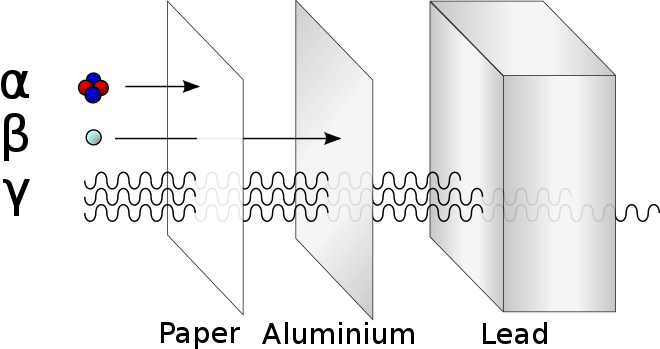

In 1899, Rutherford jumped on the bandwagon; discovering that actually, there wasn’t just one, but 2 kinds of radiation given off by radium.

The first one, called an ‘alpha (α) ray’ consisted of heavy particles that have a positive charge (named α-particles).

The particles constituting the other ‘beta (β) ray’ are much lighter and possess a negative charge (named β-particles which are infact just electrons).

Yet, this didn’t seem to complete the whole picture.

In 1900, Villard was investigating the radiation emitted by radium salts via a narrow aperture in a shielded container. This radiation was focused onto a photographic plate, through a thin layer of lead.

He used lead as it was known to stop alpha rays.

But, Villard found that even when you eliminated the α-rays with a lead screen and swept the β-rays away with a magnetic field, there was still some remaining radiation.

This residual radiation had an immense penetrating power without having any charge.

Relative penetrating powers of α, β, γ radiations.

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radiation)

Being the modest man he was, Villard did not seem to suggest a specific name for his discovery. But, when Rutherford confirmed the existence of these rays in 1903, he just couldn’t not name them himself.

So, like any good physicist, he stuck to the most ‘innovative’ name possible.

Since the Greek letters α and β were reserved for the previously discovered radiations, next in line was the letter gamma (γ). Hence, he appropriately labeled them ‘gamma rays’.

And that’s what they have been called ever since.

References

- https://www.americanscientist.org/article/herschel-and-the-puzzle-of-infrared

- Pioneers in Optics: Johann Wilhelm Ritter and Ernest Rutherford by Michael W. Davidson

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heinrich_Hertz

- https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200111/history.cfm

- https://www.lindahall.org/about/news/scientist-of-the-day/paul-villard/

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Ulrich_Villard